‘I was injured while policing a 1970s clash between skinheads and punks in Birmingham city centre’

This article contains affiliate links. We may earn a small commission on items purchased through this article, but that does not affect our editorial judgement.

and live on Freeview channel 276

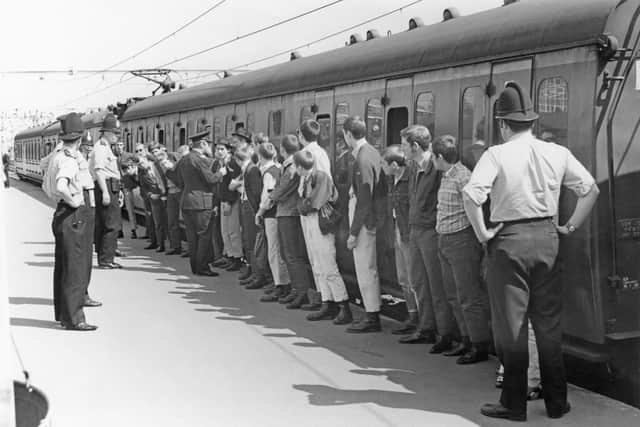

Birmingham city centre was once a simmering gathering place for “tribes”: gangs who wore their allegiances on their denim sleeves.

In the late 1970s, there were skinheads, bikers, punks, even a scattering of retro Teddy Boys. And on Saturdays, with the heart of our city packed with shoppers, tribal tensions spilled over.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn Saturday, December 15, 1979, the pack mentality turned into mass violence. What is still known as the Indoor Markets battle involved 150 youths, 20 police officers and 25 city centre security personnel. It took place in full view of families hunting for a bargain.

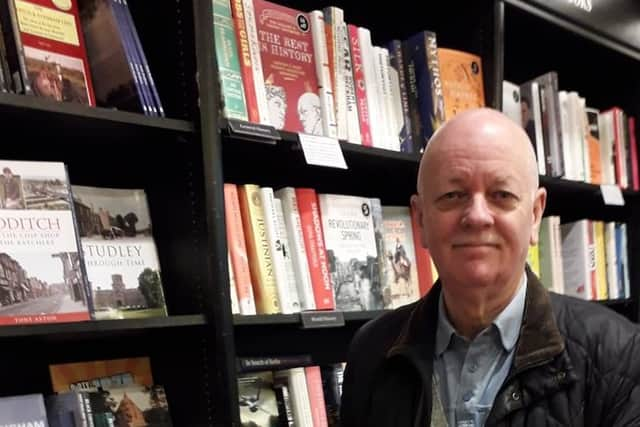

Former chief superintendent Mike Layton – injured in the violence – outlined the power struggle between gangs and their allegiances in his book, Birmingham’s Front Line. And he revealed the steps taken to prevent them settling scores on Saturday afternoons.

The names of the tribes are still familiar. Skinheads. “The youngest age group,” said Mike. “Numbers fluctuated weekly, depending on which football team was playing at home. They were responsible for the majority of disturbances, offences of assault and minor robberies in the city centre.”

Punks. “Much smaller in numbers and did not cause a great deal of trouble. However, due to their exhibitionist tendencies, they tended to attract attention to themselves.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMods. “Still emerging as a group identity and initially caused no major problems.” Bikers and Teddy Boys. “The Teddy Boys were a group of about 25 seen every Saturday. On their own, their numbers were not sufficient to cause serious trouble. However, when grouped together with bikers they became much more aggressive.”

A mixture of the groups in one concentrated area invariably proved a violent cocktail. “The public order on Saturdays, in particular, revolved around an average of some 200 youths from these groupings and it was our job to sort them out,” said Mike.

“Normally, public order problems were dealt with by officers in uniform, but I decided we needed to get up close to them, so we would stay in plain clothes. It was a risky strategy, but I had confidence in the team and our ability to control situations, even if outnumbered.”

The battle-lines for December 15, 1979, had been drawn. It was an afternoon when all factions collided and the fists and boots flew. One paper reported: “A security man and a police sergeant were injured and 18 youths arrested as gang violence plagued Christmas shoppers in one of Birmingham’s Indoor Markets.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Mothers with children, pensioners and families out buying presents became embroiled in the disturbance at the Bull Ring Indoor Market. At its height it involved as many as 150 youths, 20 West Midlands policemen, 20 security men and five corporation markets department security men.”

The article added: “It was the second week the gangs of youths – many dressed in the jeans and jackets of Hell’s Angels – caused trouble in the area. Last week stalls were overturned and produce scattered as fighting spread.”

Mike Layton recalled the day. He said: “At 2.35pm, I was with three of the team in the Outdoor Market area and observed a group making their way towards the glass doors leading into the Indoor Market.

“As they were about to enter, some of the group pounced on a young mod and started punching and kicking him. Everyone surged through the doors as he tried to escape from his attackers down some steps into the market, which was crammed with stalls and shoppers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We ran after them and, as we did so, I ran through one set of doors and straight into the screaming melee. My team went through the adjacent set of doors and, in that instant, we became separated among the crowds of ordinary shoppers.

“I jumped on one of the attackers, shouting ‘police’ as loud as I could, and he lashed out, punching me. We fell to the floor in the struggle and I hung on with him on top of me. I was now the centre of attention, with various boots flying in my direction. Fortunately, my prisoner, a 22-year-old from Quinton, took most of the kicks. A market police officer ran forward and was also assaulted.

“After what seemed an age, the crowd parted and my team seemed to fly over the heads of the attackers. Four more arrests were made and the rest scattered as uniform officers arrived.”

Luckily, Mike suffered only bruising. He added: “Secretly, I think the team felt a bit guilty that I had got a kicking, but it was not their fault and, apart from some initial banter, I chose not to give them a hard time over it. My attacker, who later got sent to prison for a month, kept apologising profusely and showed real regret for his actions.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe battle to tame the tribes was gathering pace. On New Year’s Eve, 1979, a 50 strong skinhead mob was dispersed in the Bull Ring. There was still trouble, however, and officer Bryan Davis recalled one incident: “We turned up at a huge fight in John Bright Street and jumped out of the panda car to start separating people. These were not occasions for taking prisoners as we didn’t have the numbers, so people were told in no uncertain terms to ‘move on’.

“We made a mistake in that we left the windows of the police car open. When we got back to it, a number of people had urinated through the windows all over the seats. We didn’t repeat that mistake.” *Birmingham’s Front Line, published by Amberley Publishing, is available on Amazon.