Crime files: Former police officer looks back at the 1985 football riot at Birmingham City Football Club

and live on Freeview channel 276

It was football’s blackest day, an orgy of sickening violence that left one schoolboy dead and 545 people treated for injuries – 145 of them police officers.

Such was the scale of the trouble surrounding Birmingham City’s May 11, 1985, fixture with Leeds United, Mr Justice Popplewell described it as “more like the Battle of Agincourt”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt occurred during the height of the cancer of football hooliganism, but what unfolded that day eclipsed anything that had gone before. More than 120 arrests were made before, during and after the match and trouble spilled into the city centre. Cars were smashed, seats inside the ground torn up and bottles hurled at police officers.

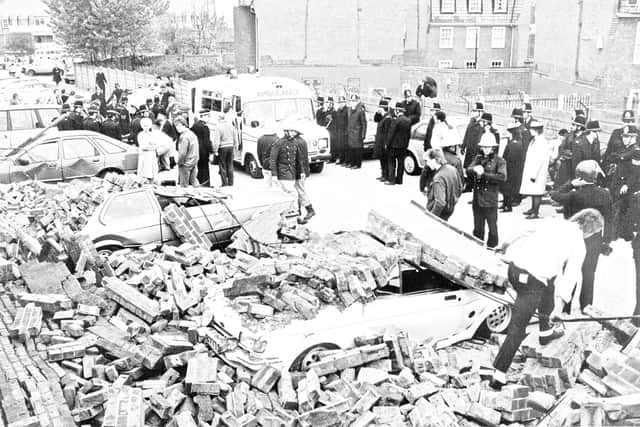

Tragically, 15-year-old Ian Hambridge, from Nottingham, was crushed when a wall at St Andrew’s collapsed under the weight of baying mobs. Many injured police officers were taken to East Birmingham Hospital and the consultant in charge of the A&E department later commented: “One of the things that impressed me the most was the stoicism and calmness of the injured policemen. They were remarkable.

“They were less concerned with their damaged heads, crushed feet and other injuries than with trying to help other people. If this is the typical British ‘bobby’ we have every reason to be proud.”

Tensions between rival supporters had been simmering long before the crunch fixture – the final match of the season. If Blues won they went top of the old Division Two and rumours swirled that Leeds hooligans intended to prevent that happening by sabotaging the game. Police expected trouble.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdStephen Burrows, who would rise to the rank of chief superintendent, recalled: “A couple of days before the match I was sent to Sheldon Police Station and bumped into the Football Intelligence Officer who asked me if I was going to be at the Leeds match that Saturday. He then confirmed there were going to be big problems and the Leeds fans intended to attend en-masse to mark the end of the season with a big fight.”

As Stephen took his place at the ground’s Railway End, he knew trouble was brewing. “I could taste it, never mind sense it,” he remembered. “As I looked around the ground the situation was not looking promising.

“I could see there were already several thousand Leeds fans in the ground. It was a volatile mood and some were already throwing missiles. I recall parts of seats flying over the fence, together with other objects, and some ‘fans’ then proceeded to remove the roof from the hotdog stand, passing it down the terraces over their heads before throwing it over the fence.

“As I viewed the gathering crowd in the seats at the Railway End, I started to spot familiar faces. Not excited youngsters, but a selection of those local troublemakers with whom I’d regularly crossed swords, many of whom were members of the infamous Zulu Warriors.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Such was the number that it gradually dawned on me that they had arranged to infiltrate the Railway End in numbers, where there was no fence. To this day, I believe the day’s subsequent events had been orchestrated to some extent between the Zulu Warriors and the Leeds fans in advance.”

The first pitch invasion took place on the half-time whistle, described by police as a mere “scouting mission” for what was to follow. At the end of the 90 minutes hundreds poured on to the pitch from the Railway End, seats were hurled like missiles. Stephen was struck by one, thrown at close range, as the battle ebbed back and forth.

“The day was saved by the West Midlands Police Mounted Section,” he said. “Whenever I watch a historical film depicting battle with cavalry, I’m reminded of that moment. I quickly appreciated the effectiveness of horses against foot soldiers.

“It was like the Charge of the Light Brigade, especially the white horse that continually rode backwards and forwards, knocking the hooligans over like ninepins. The horses drove the mass of the invaders inexorably back towards the stand.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Encouraged by this development, we were formed into a line with truncheons drawn and mounted a ferocious foot charge and in a beautiful moment of poetic justice, I came face-to-face with the seat thrower who had injured me earlier.

“We finally beat the pitch invaders back into the seats and I can remember a number of them being hauled up onto the upper tier by others in order to escape due process.”

The battle inside the stadium had been won. It was now time to tackle the spiralling trouble on the streets. Stephen said: “There were about 30 of us in various states of injury and exhaustion, none of us having any riot gear as yet. We exited the ground into Garrison Lane. In those days you came out onto a road that led to a children’s playground set at a much lower level than was visible from where we were standing.

“About 100 yards away I could see about 40 youths milling about and the Chief Inspector decided that another baton charge would be appropriate. We formed into a line, drew our truncheons and with a blood-curdling cry off we went.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“As we got closer, the hooligans began to run, disappearing out of sight over the edge and down the drop into the playground. As we drew closer to the playground, it began to become visible. This revealed a daunting prospect as we realised the playground was occupied by several hundred youths busily ripping the swings out of the ground to use as weapons.

“We were forced to withdraw as our pursuers stopped to turn over a police van, which probably saved us as reinforcements arrived in the form of a phalanx of police motorcyclists, having the advantage of crash helmets and full leathers. As luck would have it, the overturned van was full of shields that we liberated and joined our rescuers in chasing off the crowd.”

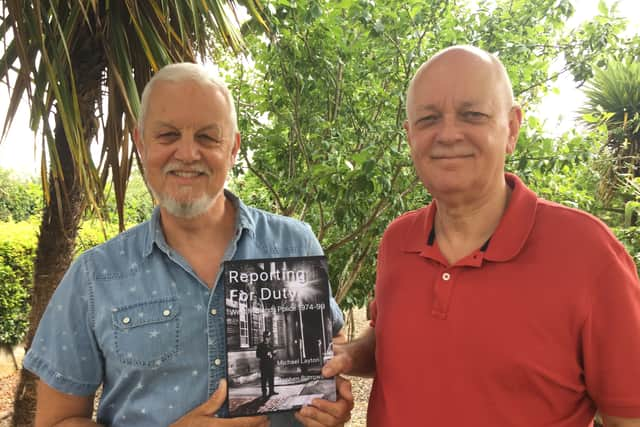

*Stephen Burrows’ recollection of the terrible day is included in his book “Reporting for Duty”, a chronicle of West Midlands Police incidents from 1974 to ’99. To get the book go to: Reporting for Duty book and it is also available from West Midlands Police Museum.